Who Attends Sprint Retrospective Meetings?

Whether remote or in-office, sprint retrospectives are the only agile meetings that are explicitly about improving processes as a team. But who attends sprint retrospectives?

A lot of really juicy information gets discussed in retrospectives – including why a certain thing went wrong or what the team is struggling with. And because of that, a lot of people might want to drop in and take part.

But be warned – prying eyes can ruin a retrospective!

In this guide, we’re running through who should participate in a sprint retrospective, and what each person’s role is within the meeting.

We’ve included two structured conversations to help you politely handle the conversation when someone asks to join your retrospective or drops in unannounced.

This guide is broken down into the following sections:

The goal of sprint retrospective meetings

Sprint retrospectives are designed to help teams build a habit of continuous process improvement. This is all part of the agile/scrum philosophy of making continuous iterations and continuous improvement.

Retrospectives are closed team events that usually serve two key purposes:

- Identify what worked and what didn’t from a team collaboration perspective.

- Create space for suggested improvements and commitment on next steps.

Because retrospectives deal with sensitive topics about the quality of team-work and processes, emotions can flare up, so agile teams need to cultivate psychological safety so people feel they can be honest about problems and get to a solution without feeling threatened.

Who attends sprint retrospective meetings?

Sprint retrospectives should only be attended by the people who executed on work in the sprint.

That includes:

- The sprint leader: Scrum Master, or Product Owner

- People who executed on the work: Engineers, Developers, and Designers

The retrospective facilitator (often the Scrum Master or Product Owner) is responsible for running the meeting and keeping it on time. Everyone else participates, offering their views on what happened (good and bad) and how the team can improve for next time. And that’s about it.

Retrospectives are not meant to be huge, strategic meetings that change the direction of the organization. They’re about taking a look at a small increment of work and making small changes to improve teamwork, collaboration, or processes, bit by bit.

Exceptions:

While sprint retrospective meetings are intended to serve only the team who executed on the sprint, there are three exceptions where other people might need to join the meeting.

- New Scrum Masters in the company: They might sit in and observe to learn how the company runs retrospectives.

- The Product Owner: They might even run the retrospective in your organization, but broadly they may want to participate if they also took part in the building process (i.e. not just in a leadership/management role).

- The CTO or CEO in very small organizations: This is a very rare exception, typically only in small startups, where the CTO is an active member of the sprint team shipping code on a regular basis (not just troubleshooting) or may implicitly take on the role of Scrum Master or Product Owner.

Who should not attend a retrospective meeting (and why)

Anyone who is not a member of the Scrum team or sprint execution team should not attend a sprint retrospective.

There are two key reasons why:

- They are unhelpful in retrospectives because they are a few steps removed from the work (too many cooks in the kitchen)

- Their presence damages the retrospective process by undermining its authenticity and the ability for team members to be vulnerable (power differentials)

Groups that are unhelpful in sprint retrospectives

If you have too many cooks in the kitchen, the retrospective can’t function properly.

Broader team members who didn’t execute during the sprint

Retrospectives are made for the execution team to identify what worked, what didn’t, and how to improve. Anyone who didn’t take part in the retrospective likely wouldn’t be able to contribute meaningfully to this goal because they did not perform the work and therefore cannot credibly comment on it.

Non-team members, regardless of their contributions to the sprint

Even if a sales, marketing, HR, or other team member took part in a sprint, a retrospective is explicitly and exclusively about working towards improvements for a specific team. Non-tech members might have different needs and reflections, so they would be better served holding their own retrospectives to get insight into their own specific processes. You can check out Parabol’s guides on Running an Asynchronous Retrospective or Leading an Agile Retrospective on Remote Teams for more information.

Groups that could damage the retrospective process

When there are power differentials at play, retrospectives lose their meaning and psychological safety gets undermined.

Management teams or C-Suite executives

A sacred part of the retrospective process is openly and honestly calling out what didn’t work so you can fix it. Management teams and C-Suite execs might be interested in that if they think a team is under-performing or has an irresolvable tension. But participants might be worried that anything they say will be used against them in performance reviews. This looming threat can seriously damage the psychological safety of the team and creates an incentive to only talk about the good stuff, which undermines the point of holding a retrospective.

Human resources

Similar to having management in the room, HR can undermine the culture of a retrospective. Even in the best case -–that HR is curious how these meetings run so they can recruit better – there’s a risk of misinterpretation and broken trust that ruins the retrospective.

How external participants damage retrospectives

When someone shows up to a retrospective who isn’t supposed to be there, there are five key risks:

- Psychological safety is lost or damaged: People need the freedom and security to be honest and forthcoming in retrospectives. Extra attendees dropping in crushes the team’s hard-won bonds of trust and can be particularly damaging for introverts.

- Irrelevant extra information throws people off: Retrospectives run on a very specific agenda, and it’s easy for “just a quick thought” from an outside voice to throw everyone off course.

- There are more opportunities for emotions to run hot: More people means more opinions that can push someone over the edge. This can be especially painful coming from someone who didn’t actually take part in the sprint but has the power to punish someone for doing something wrong.

- It changes the focus of the meeting: When there are extra people in the meeting, participants focus on that person’s presence more than the topics that need to be discussed in the meeting. One external person can distract the whole team and create an incentive to run a ‘rosy-retrospective’.

- There’s room for misinterpretation: Retrospectives run in a way that might seem odd to people who aren’t used to them, which leaves space for misinterpreting what was said. This doesn’t mean there’s any malice – it just happens and causes damage all the same. To hedge against this, you might also find yourself wasting time explaining context for the extra person in the room.

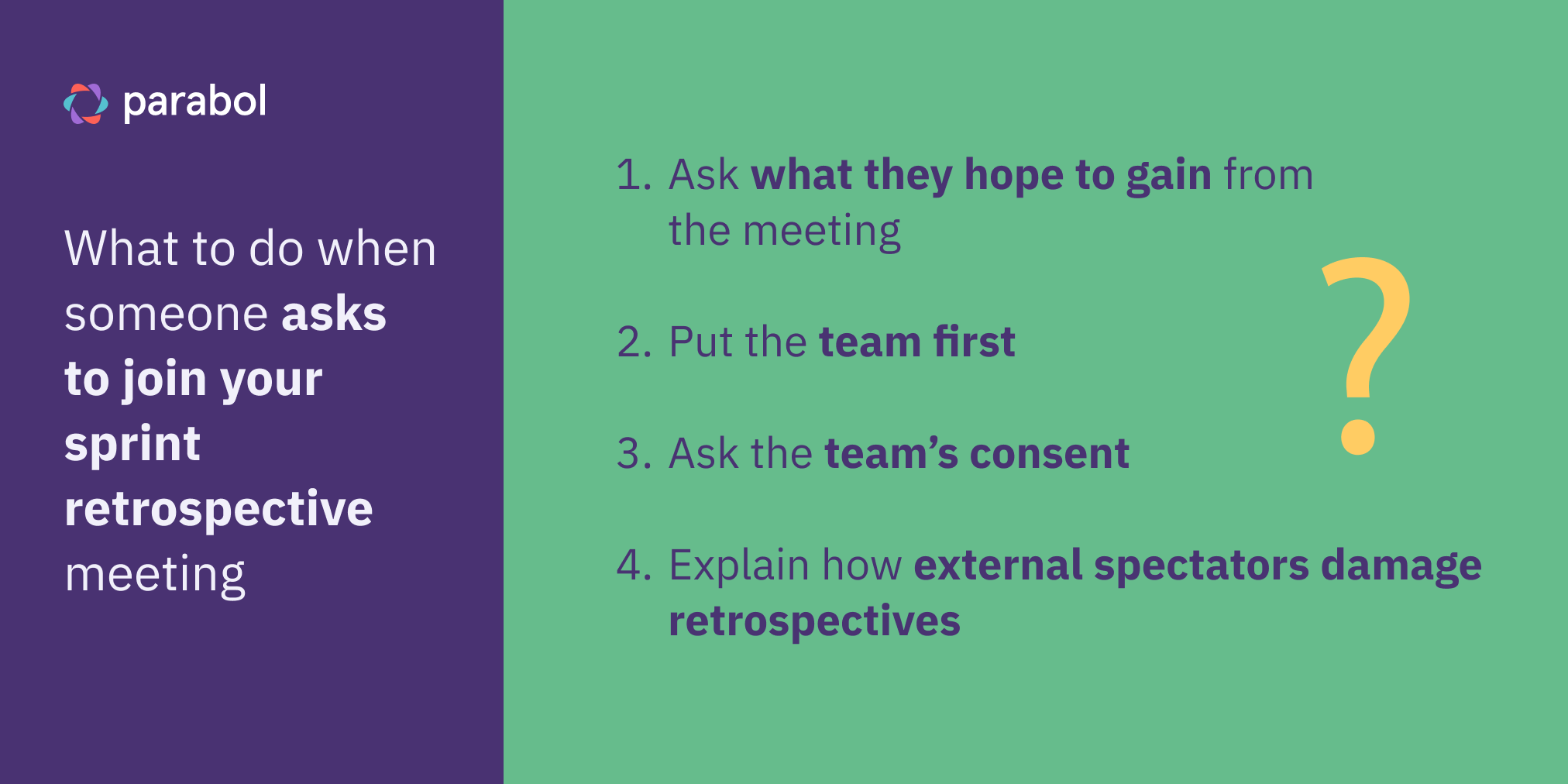

Structured conversation 1: What to do if an external person asks to join the retrospective

If you’re running a retrospective and someone asks to join that shouldn’t be there, you have a few options available to you. Here’s how we suggest approaching the conversation.

1. Ask what they hope to gain from the meeting

Many people are just curious or want to know what a team is struggling with and what iterative improvements the team is committing to in retrospectives. In these cases, you can offer to provide a summary after the fact. There’s also the possibility that they want information that isn’t discussed in a sprint retrospective (for example, the plans for next sprint – which are put together in the sprint planning meeting). In these cases, you can direct them to the right resources.

2. Put the team first

If the person insists they should attend the actual meeting, reiterate that the retrospective is not meant to be a big show – just a small team meeting where they talk about improving how they work together. It’s not a larger strategy session and the outcomes of a sprint retrospective won’t have a wider impact beyond the team, so it’s not necessary for anyone else to join. Explain that the retrospective relies on the team being vulnerable to each other, and participation of an external party could undermine psychological safety.

3. Ask the team’s consent

If there’s a legitimate reason why someone might need to attend a retrospective (such as a new Scrum Master who wants to sit in) provide notice ahead of time to help your team prepare. If you can, give your team a couple of date options of when that person can attend – that way the team can make their choice, get through it, and move on.

4. Explain how external spectators damage retrospectives

If the person does not have a legitimate reason to join the meeting, reiterate the point of a retrospective meeting and mention the ways in which external spectators can damage the process.

Source: Comic Agile

Source: Comic Agile

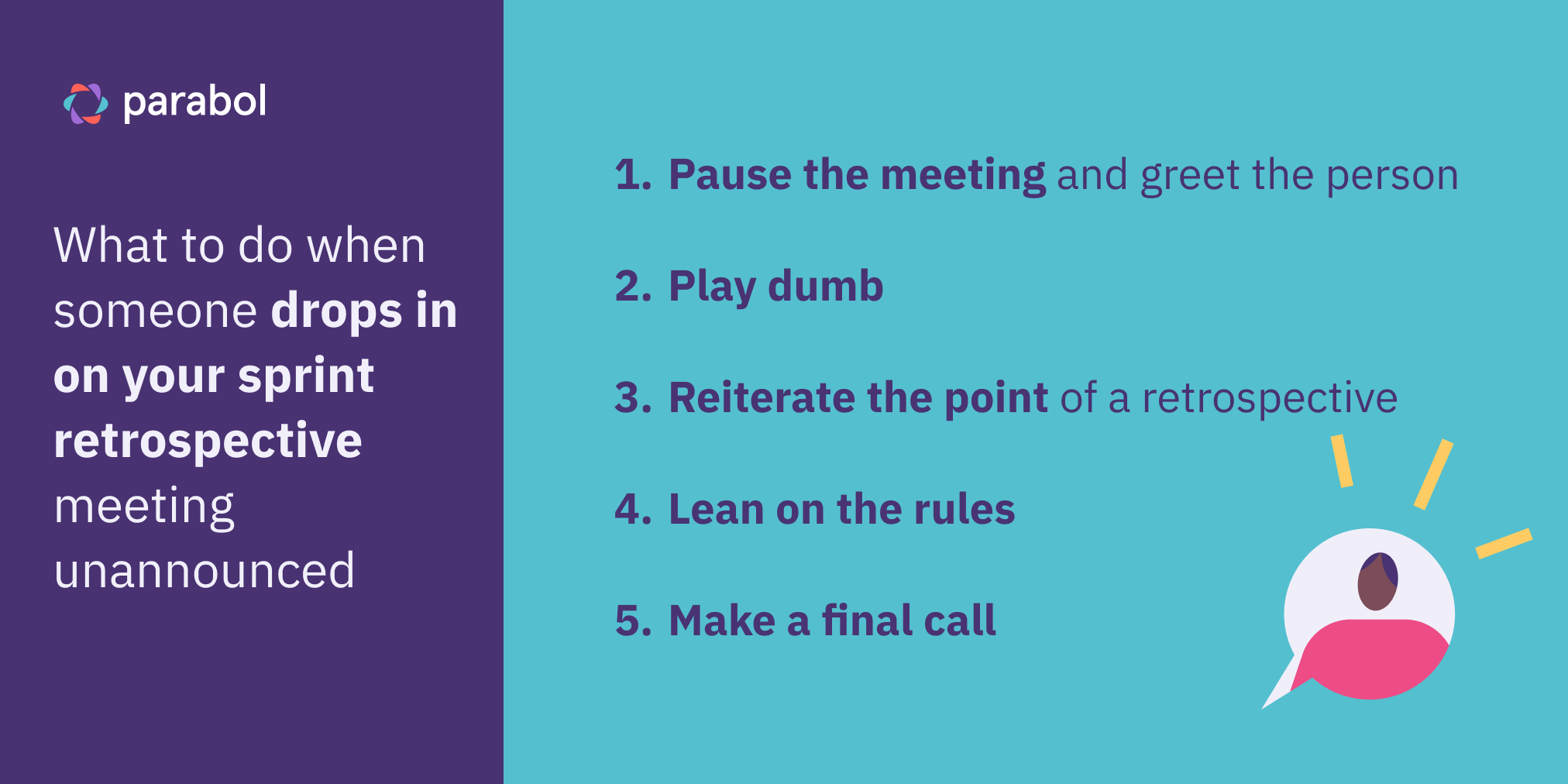

Structured conversation 2: What to do if someone drops in on a retrospective unannounced

If someone shows up to a sprint retrospective unannounced to join in or observe, here’s how to politely handle the conversation and turn them away.

1. Pause the meeting and greet the person

Use the clear pause to implicitly call out their presence and show it is a disruption. Often, this is enough to get someone to realise they aren’t supposed to be there.

2. Play dumb

When the meeting is dead silent after you stop to pause, tell the person you are in the middle of a meeting, but you’d be happy to send them an email, Slack note, or have a quick chat with them after the fact about anything they need. The key is to pretend the person isn’t there for the meeting, but is instead there to talk to you personally about something. That draws the attention away from their “jumping into” the meeting and brings it squarely back to the fact that it’s not a good time for you to talk.

3. Reiterate the point of a retrospective

If the person insists they are there just observe (“just pretend I’m not here!”), publicly reiterate that sprint retrospective meetings are private, and intended for the team only. Again mention you’d be happy to send them a summary after the fact so that person gets the information they need. Or offer to facilitate a retrospective for them and a group of their own colleagues, if they want to see how the process works.

4. Lean on the rules

If this person isn’t getting the hint, you can lean on the “formal rule” that no one except the team who executed on the sprint is allowed in retrospectives, so unfortunately they won’t be able to stay. This can be very tough if the person who dropped in is aggressive or tries to pull any form of authority over you and the meeting. However, you can reiterate that the goal of the meeting is for the team to talk about how they work together, and that requires a team-only setting. Further, stress that it’s about the structure of the meeting itself and it’s not personal. Anyone would be asked to leave, so it has nothing to do with that person on an individual level.

5. Make a final call

If the person absolutely insists on staying in the room, you have two choices:

- Wrap up the meeting early: Use the extra time to have a private sit down with that person about the point of a retrospective and ask them to not drop into meetings in the future.

- Continue the meeting as-is: Realise the team is likely going to shut down and not share as openly as they otherwise might have. Ask to speak to the interruptor privately after the meeting.

Sometimes option 1 is not possible and you’re stuck with option 2. In these instances, follow up with your team after and give them an additional time to discuss remaining issues in more detail if needed. That way you salvage as much of the retrospective process as possible.

In both cases, you should always follow up with the person who dropped in, or someone above them, to explain once again why it is not acceptable to just drop in and ensure they don’t do it again.

If you use an online retrospective tool like Parabol, it’s much more difficult for a person to jump in unannounced, since you must first invite them to your team.

Creating space for honesty, trust, and improvement in your sprint retrospectives

The sprint retrospective process goes beyond the individual and focuses on how a specific team, working on a specific technical project can iterate for the future.

Within the Scrum framework and agile methodology, everyone has a unique part to play.

Even in a big physical space (a meeting room), there is only so much metaphorical room and only so many voices that need to be heard at a given time.

With too many people – or the wrong people – present, you run the risk of catastrophe for everyone involved.