What is Transparency at Work?

Our clients were a new management team in charge of marketing for a multi-billion dollar consumer brand. They had just brought the majority of their creative and production in-house to keep up with the insatiable pace and demand of the internet. My team and I were hired to help them stem their 30% attrition rate – people were leaving just as quickly as they could hire them.

The management team had repeatedly heard in exit interviews from departing staff that the department wasn’t “transparent” enough. Folks didn’t feel they were trusted with information or making decisions. We were asked, “can you help to make our department more ‘transparent’?” We began by listening.

When we’d meet with our executives to gather information on the department a curious thing would happen: our conversations together would be serious but pleasant. However, later on in the afternoon one of us on the consulting team would get pulled aside into an office by an executive to hear “the real story.”

It became clear to us that leadership didn’t trust one another very much. Our work would have to start at the top. We offered our observations, suggested an offsite meeting, and were delighted when they accepted.

To build trust we’d first have to build intimacy. An ingenious colleague of mine, Athena Diaconis, suggested we write a curated subset of the 36 Questions That Lead to Love appearing in The New York Times on the interior panels of a paper fortune teller, pair off our executive leaders, and force them to open up to one another.

10. If you could change anything about the way you were raised, what would it be?

The questions themselves are derived from an academic study by Arthur Aron, et al. The Times describes his group’s findings thusly:

…mutual vulnerability fosters closeness. To quote the study’s authors, “One key pattern associated with the development of a close relationship among peers is sustained, escalating, reciprocal, personal self-disclosure.”

We were surprised by the immediacy of the effect of our exercise — there were laughter, tears, and embraces — as well as lasting change: from that day forward our executives began to behave less as self-interested individuals but more as a team. It was like night and day.

Intimacy is a form of interpersonal transparency and as will be argued, a prerequisite for other forms of transparency at other levels within an organization. But what does transparency even mean?

What transparency isn’t

Understanding transparency and how to apply it can more easily be seen when it stands in contrast with what it isn’t:

Secrecy: the intentional or unintentional withholding of information

Some information is kept private explicitly. For example, “the budget is only available to people who are vice president level or above.” Other times, information is simply inaccessible because it’s never been published in a place others have access to such as on a private storage device or as an attachment sent to only a few people.

Ambiguity: uncertain or inexact information

Ambiguity can arise in at least two forms. One form is implicitness. It’s like when the boss says, “we need to get this report done by Friday,” and given the context it’s understood to mean, “you need to get this report done by Friday.”

A second form of ambiguity is ephemerality: when information may be specific, but its record is fleeting and impermanent. It’s like when the boss says, “I expect you to prepare these reports from now on,” and that additional accountability cannot be weighed against others the employee may already have.

What transparency is

If we flip our via negativa definition of transparency on its head we can say:

Transparency is the ready availability of explicit information.

What else fits this description? The internet.

Within the span of a single generation, we’ve gained the ability for nearly everybody on earth to transmit large quantities of high-fidelity information to one another. Most IT professionals and politicians are kept up at night by what might be exposed to the public at the push of a button. These organizations and individuals can only be hurt by information leaks. In the future, perhaps the organizations which succeed most will be defined instead by how much information they are able to share.

In the end, greater transparency is a design choice. With all design choices there are trade-offs: the minimization of secrecy and ambiguity will come with other costs. So, if it’s not a panacea, why encourage transparency at all?

Levels of transparency

Seen as a design choice, transparency can be applied at varying levels within an organization:

- The Individual: held as a value

- The Team: applied as a set of practices

- The Organization: activated as a strategy

We’ll explore each of these levels with examples.

Individual transparency

Activating transparency within a culture begins with each individual. Transparency is a value. People do it because they believe in it. There isn’t one correct way to be transparent. For some, it may mean feeling as though they are able to bring their whole emotional selves to the office. For others, it may mean sharing their successes and failures and making requests to get what they need.

Values cannot be dictated from the top (The Onion)

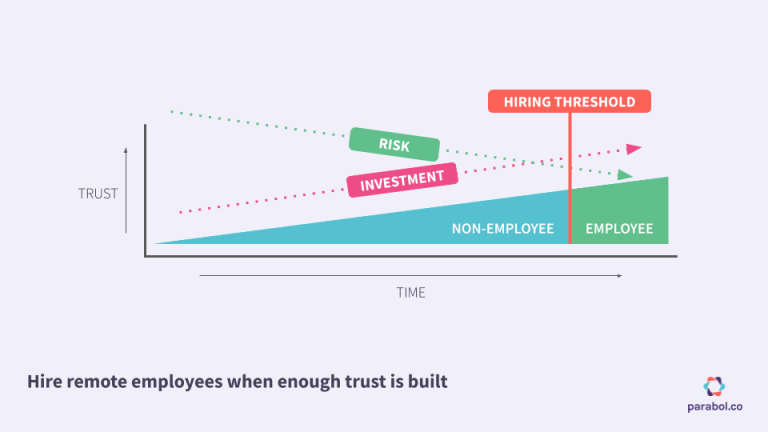

Installing a new value within a culture is notoriously challenging. It cannot be solely dictated from the top. Consider, for example, the number of failed (and ongoing) attempts at “nation-building” which attempted to install democratic values via regime change and coercion. Within an organization, change must equally be bottom-up as it is top-down. Each existing employee must understand, give consent to, and be incentivized by the new value. Every new employee must be hired in equal parts for skill competency and for value alignment.

Although difficult, the benefits of holding transparency as an individual value to build an emotionally authentic and safe working environment is just beginning to be experimentally confirmed. In 2013, Shanock et. al published a study entitled Less acting, more doing: How surface acting relates to perceived meeting effectiveness and other employee outcomes. They demonstrated workers who believe their colleagues are acting authentically also perceive their meetings as being more effective. In March 2016, our company Parabol replicated their findings and added evidence that workers who themselves feel they can be their “full candid selves” at the office also believe their meetings are more effective. Intuitively this makes sense: acting is exhausting.

Emotional honesty is only a single expression of transparency. Sharing one’s experiences and needs is another. An example of how transformative this habit can be is illustrated by my good friend spencer wright.

Spencer publishes a weekly newsletter, called The Prepared (from the adage, “fortune favors the prepared”). It was born out of his interest to stay current on developments in manufacturing, technology, business strategy, and product management. Along with curating articles on these topics, he also shares earnestly about his career progress, personal state of mind, and projects he’s working on. He’s near Jeffersonian in his output. At times, it hardly seems he has a thought he doesn’t write down.

Publishing each week engaged Spencer in a feedback loop that has guided his life’s trajectory. In 2012, he began writing about The Public Radio, an FM radio project that he was developing with childhood friend Zach Dunham. In 2013, a bicycle part — a seatmast topper optimized for 3D printing in titanium — started showing up on his blog as well. His exploration resonated with his audience. The following year he was invited to write for the 3D printing industry’s leading trade publication, the Wohlers Report. Throughout he’s received numerous speaking opportunities and job offers. In 2015, he joined additive manufacturing software company nTopology. Sharing regularly led to a new career.

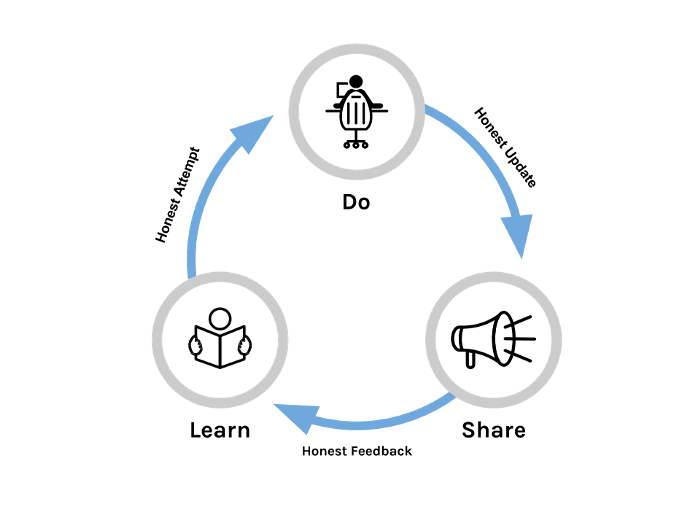

The feedback loop created by practicing individual transparency

Spencer’s ability to materialize a community out of the ether is a testament to the power of self-publishing on the internet. This degree of transparency takes courage. Being engaged with an audience can create a tremendous sense of responsibility. In Spencer’s own words:

Yesterday, I committed to spending $1600 on testing for my EBM seatposts. That’s more than I pay for rent, and I spent a while considering whether it was a wise purchase. But a few months ago I wrote a blog post that ended with “More updates soon,” and now I’m accountable for that. Publishing has definitely made me work harder and think more about my say/do ratio — which are, at least at the current juncture, good things.

There are downsides though. Namely, I’m continually pushed to invest more of my time into things that don’t have any immediate payoff. I’m confident most of this investment is worth it, but sometimes I feel anxious that it won’t add up to anything tangible. However with The Public Radio relaunching, the possibility of a commercially viable 3D printed bike part in the works, and an amazing network to help build nTopology’s user base, these anxieties are pretty small.

Spencer’s publishing practice could be viewed as an extreme form of an Agile stand-up meeting: he broadcasts what’s changed, what he’s about to do, and what obstacles stand in his way. Even without a closely coupled group of co-workers to help him, he has got what he’s needed to grow.

Team transparency

Communicating clearly and openly between team members depends on one simple but fundamental practice: writing everything down. Many teams’ members are sunk by not knowing the plan, the process, the team’s roles, and resource limitations. It’s surprisingly easy to fix: open a shared document and start typing.

But what should be prioritized to be written down? We can divide these opportunities for greater transparency into two areas:

- Transparency internal to a team, with its members

- Transparency external to the team, with its stakeholders

In the table below, some suggestions to begin with:

Each of these practices deserve to be written about in detail individually. Until then, a summary is offered below.

A plan. Often plans are developed solitarily as heavily produced slide decks or detailed Gantt charts and presented as unchanging gospel. For work with an uncertain outcome (for example, launching a marketing campaign or designing a product) a detailed plan may not be appropriate or possible.

A more transparent way to plan is to collaborate on defining individual objectives and working backward across three time horizons such as 2 months / 2 weeks / 2 days. Simply gather your work mates and ask them, “two months from now, what should we have completed?” Then, “two weeks from now, what will we have done to prepare us for success two months from now?” And finally, “what are our first actions to complete two days from now and who will own them?”

Policies and permissions. Teams of people, like any civil society, need rules to give members guidance on how to behave. Traditional enterprises often operate by an implicit master rule, “do nothing new without asking permission of a superior.” Newer, more responsive organizations often turn this policy on its head as, “act first, and we’ll legislate out what has been shown to cause us harm.” No matter which you elect, be explicit with what your team’s default policy is.

As your team operates it will generate tensions. Colleagues will want to be included in decision making or revision cycles. Budgetary authority will need to be clarified. The antidote to resolving these tensions is to meet on a regular rhythm and record new rules in the form of policies or permissions. Conduct retrospectives on a monthly or bi-monthly cadence to revise the existing rule set.

Roles. Along with generating new policies for the team to operate under, working together will cause new expectations to arise. Who at the office is supposed to stock the refrigerator? Who’s supposed to pay vendors? Who is sourcing new sales opportunities? Historically teams have relied upon job titles or job descriptions to exhaustively capture a worker’s responsibilities.

Newer, more transparent organizations clarify roles continuously — often within team retrospective meetings. August Public, an organizational transformation consultancy, continuously revises and updates their team’s policies and roles for all to see (they call this process “governance”).

Projects & Actions. All of the above practices concern themselves with working on the strategy and structure of the team, but how does one perform work itself with greater transparency? I recommend the check-in meeting format to process larger objectives into bite-sized pieces, set ownership on who’s accountable for what outcome, and see who needs help from each other. Here’s how it goes:

- Get together at the head of each week, set a brisk but firm time limit

- Share what’s changed from last week

- Bring new agenda items from the plan or from new needs

- Process these agenda items into projects with a single owner and record them in a shared document

- Get out of the meeting and get to work

A check-in isn’t a company all-hands meeting. If your team struggles to make it through the meeting, your team may be too large. At Parabol and in previous client work, we recommend a guideline of trying to limit team membership to no greater than 10.

Friction can arise between teams from a lack of information flow. Two practices can help teams resolve these external tensions: publishing regular progress and publishing an API.

Publishing progress & changes. As a counterpoint to the check-in meeting, publishing a brief update to external stakeholders on what’s been accomplished is a simple mechanism for keeping an organization informed and giving team members a true sense of momentum. At Parabol, we call this habit a Friday Ship and publish our own progress to our broader community.

Sharing your team’s API. Unclear rules of engagement are a common cause of frication between teams. What is a team responsible for? How do I submit a work order? How do I request information?

All the way back in 2002, Jeff Bezos issued a series of mandates to his organization:

All teams will henceforth expose their data and functionality through service interfaces.

Teams must communicate with each other through these interfaces.

There will be no other form of inter-process communication allowed…The only communication allowed is via service interface calls over the network.

All service interfaces, without exception, must be designed from the ground up to be externalizable. That is to say, the team must plan and design to be able to expose the interface to developers in the outside world. No exceptions.

Bezos closed his mandate with:

Anyone who doesn’t do this will be fired. Thank you; have a nice day!

Excusing his authoritarian tone, the intended effect behind Bezos’s directive was to ask each team to itemize the resources they have, the services they offer, and establish clear interfaces between teams. He may have been talking about digital interfaces, but for many organizations a document or internal webpage would be effective.

Perhaps this mandate enabled the offering of Amazon’s internal hosting infrastructure, AWS, to the public. It’s now Amazon’s single largest source of revenue.

Organizational transparency

At the highest level, transparency is a strategy. Transparency is about engendering trust. The fewer secrets an organization keeps from the outside world, the more trustworthy that organization should be. It’s the ultimate proclamation of: what you see is what you’ll get. In an age where whistleblowers are venerated as heroes, choosing a transparent organization to work for or buy from seems like the right choice.

Knowing why an organization exists and what it stands for is the first step. Digital product makers Fictive Kin created /PURPOSE to encourage organizations to explicitly publish their purpose and values at a fixed address off of their homepage (for example, http://fictivekin.com/purpose/). In their own words:

…we think the world would be a better place if the people trying to shape it spoke openly and plainly about their vision for the future.

At the time of this writing, more than 30 organizations have chosen to list their /PURPOSE page on slashpurpose.org.

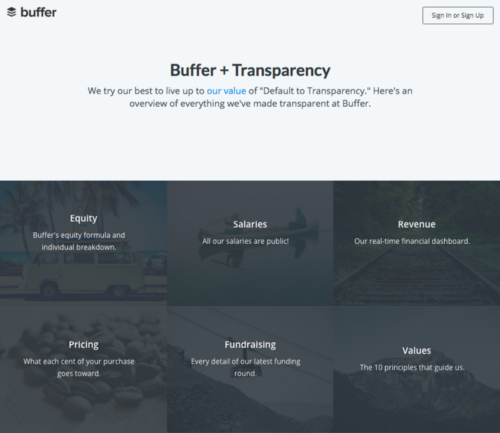

Example of Buffer’s transparency dashboard

The line for what’s considered private and privileged information is highly plastic. Perhaps no company other than Buffer illustrates how much information can be opened to the public. Emanating from their value “Default to Transparency,” they compile and update a plethora of information on their Transparency Dashboard that is still considered by most organizations too sensitive to share.

Buffer shares their worker’s salaries, revenue, pricing, and diversity metrics. Inside the the company, Buffer employees even share inboxes via a radical but smart email aliasing scheme. Even much of of Buffer’s software IP is available via open source on Github.

Evaluating Buffer critically, their radical level of transparency may be a product of category competition: there is no shortage of social media management applications. In order to attract the best talent, build the best products, and win the best customers, radical transparency may be what’s required to win. Transparency as a differentiator can be observed within other competitive categories such as retail clothing at Patagonia (see: The Footprint Chronicals) or at Everlane (see: Factories) or coffee roasting at Starbucks (see: Global Responsibility Report) and Counter Culture Coffee, among many others.

Publishing a platform others can use is also a form of strategic transparency. Whether directly or indirectly monetizable, creating a consumable service where other organizations become dependent on your very existence can be a lucrative choice. Creating a transparent marketplace, such as the Apple App Store, by creating a means of distribution, explicit publishing guidelines, and a means for extracting benefit for participation is a now classic example of this strategy. Perhaps less understood is why a company like Tesla offering its patent IP to its would-be competitors, license free, might benefit Tesla.

On June 12th, 2014, Elon Musk published a post on the Tesla blog All Our Patent Are Belong To You. On the surface, the act is completely in line with Tesla’s stated purpose, “to accelerate the advent of sustainable transport by bringing compelling mass market electric cars to market as soon as possible.” Within the announcement of the patent’s availability, Musk offers this as partial justification:

Given that annual new vehicle production is approaching 100 million per year and the global fleet is approximately 2 billion cars, it is impossible for Tesla to build electric cars fast enough to address the carbon crisis. By the same token, it means the market is enormous. Our true competition is not the small trickle of non-Tesla electric cars being produced, but rather the enormous flood of gasoline cars pouring out of the world’s factories every day.

Underlying this seemingly altruistic statement may also be a bet that by accelerating the market through offering up its IP portfolio, Tesla may itself benefit in the long run. Tesla will spend around $5 billion dollars bringing its 10 million-square-foot battery-producing “gigafactory” online in its efforts to vertically integrate. Along with the batteries Tesla will offer, Tesla will no doubt profit from offering other products to would-be car manufacturers. Tesla may recognize the rising tide lifts all boats, but especially Tesla’s.

In summary

The internet hasn’t finished reshaping society. Managers who grew up without a computer in every home and pocket have a very different relationship to information than younger generations. The first generation of children who fall asleep at night clutching their devices have a very different relationship to information than their parents. Greater transparency in the workplace may be an inevitability.

Transparency creates trust and can be reasoned about at three levels: as a value held by individuals, as a set of practices for teams, and as a strategy for an organization.

Transparency enables feedback loops. Just as spencer’s blog committed him to cycles of doing–sharing–learning to propel him forward at an individual level, so does transparency acting at the team and organizational levels.

Transparency for individuals and teams cannot be dictated top-down. Rather transparency is built by individuals who trust one another. Trust is built on intimacy. A group of individuals who trust one another can build a transparent team. A collection of transparent teams can build a transparent organization. It can’t happen any other way.

Transparency within and between teams means writing everything down so it can be evolved. Internal to a team this means writing down the plan, policies, roles, projects and actions. Externally, this means publishing a team’s progress and changes as well as its rules for engagement. It also means revising what’s written down with feedback stakeholders on a regular cadence.

Transparency may be a good strategy in a competitive category. If all organizations in a category are roughly equal, perhaps the most trustworthy organization will be preferred by job-seekers. This organization will get better people. This organization will make the better products. Eventually, the more transparent organization will win.

Time will tell if greater transparency leads to better outcomes. Like any design choice, there are tradeoffs. For one, transparency may be a sort of one way door: once adopted, it may be difficult to return to secrecy without paying a high cost. There are also real dystopian dangers, as told within Orwell’s 1984 and Egger’s The Circle. On the other hand, if you are a person who values honesty and openness a more transparent future offers a lot to hope for. Either way we will lose some things and gain some others. Exploring and reconciling these potential consequences is a conversation we should all be engaged in.

Presentation

You may view this article in presentation form on SlideShare. For your convenience, it’s embedded below:

References

Shanock, L. R., Allen, J. A., Dunn A. M., Baran, B., Scott, C.W. & Rogelberg, S.G. (2013). Less acting, more doing: How surface acting relates to perceived meeting effectiveness and other employee outcomes. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 86, 457–476. doi: 10.111/joop. 12037