Agile Management Beyond Tech

For more than a century, most office workers team up as though they are running a relay-race: a coworker gets passed the baton, they run as fast as they can, and try to smoothly tag in the next runner until their team crosses the finish line. Winning means moving faster and more efficiently than the competition. The best teams study the course and drill to make seamless handoffs.

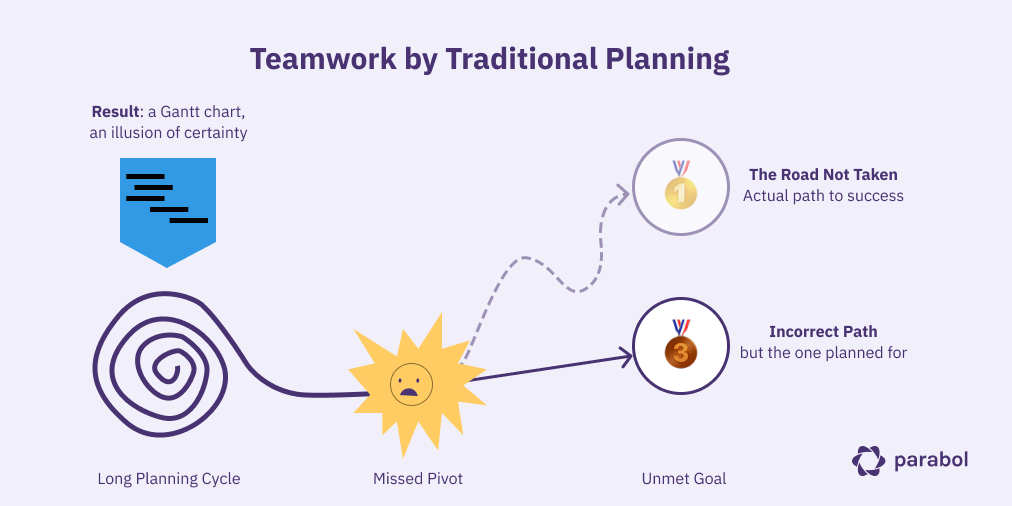

Ever since the arrival of the internet, the relay race has been more difficult to plan for. It’s as if the lights have gone out on the course and we’re all running in the dark. Victory is often driven by our ability to respond to new information rather than simply run fast. Gantt charts no longer apply.

So how might you effectively compete in darkness, surrounded by both unknown dangers and unexpected opportunities?

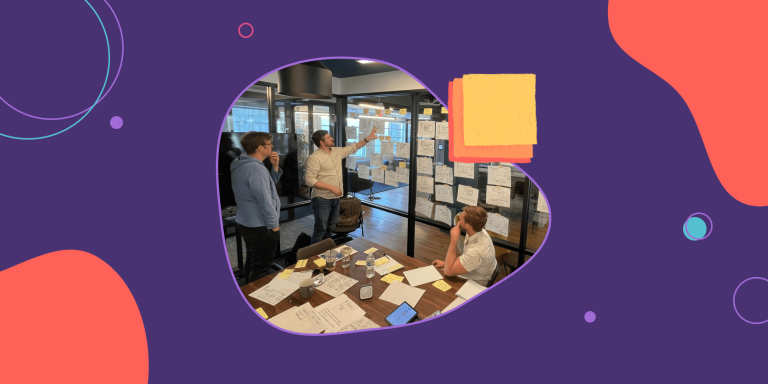

You’d probably send out scouts to see what’s around your current position. Then you’d meet, exchange what you’ve learned, and decide as a team whether to proceed, go a new direction, or start over.

Since we don’t know what’s ahead or precisely where we are going, combining team members from diverse backgrounds is more valuable than siloed specialists — and multidisciplinary teams who work well together in conditions of rapid change are the most valuable of all.

Software teams discovered this way of working a while ago – we call it Agile.

After decades of scrapping plans and schedules due to unanticipated technical challenges or changing customer needs, software teams learned to value, “individuals and interactions over processes and tools…and responding to change over following a plan”.

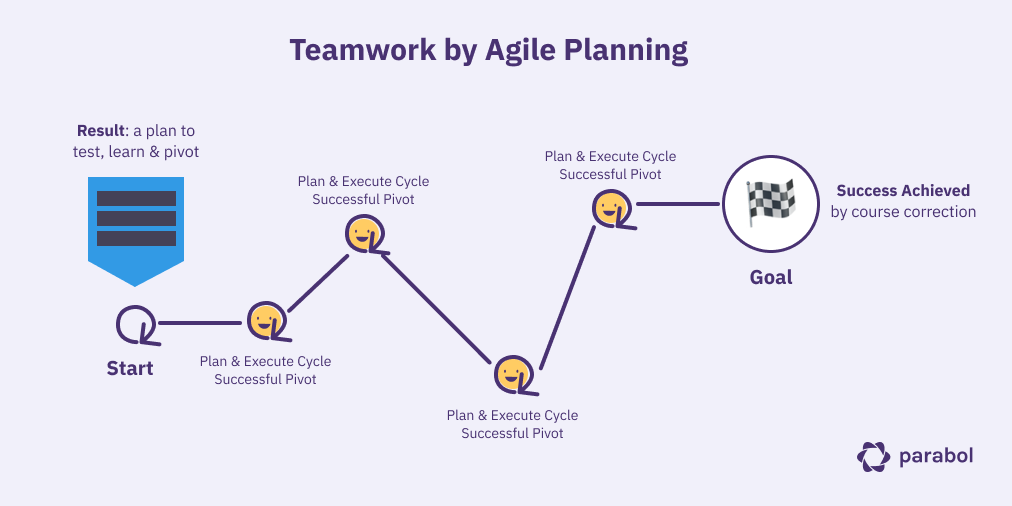

In lieu of following a strict plan, agile teams operate in short sprints: they gather a small amount of data, formulate a short-term response plan, carry it out, and use what they learn to inform the next sprint, and so on.

Outside of software, more and more teams are waking up to realize they are really running around in the dark. Long planning processes are no longer serving them and they know they must transition to a new way of working more suited for the internet era.

Indeed, some teams already have: there is a growing movement to bring Agile to the entire organization.

To bring this new way of working to your organization, you just have to follow five simple steps.

How to Navigate Uncertainty with Agile Management

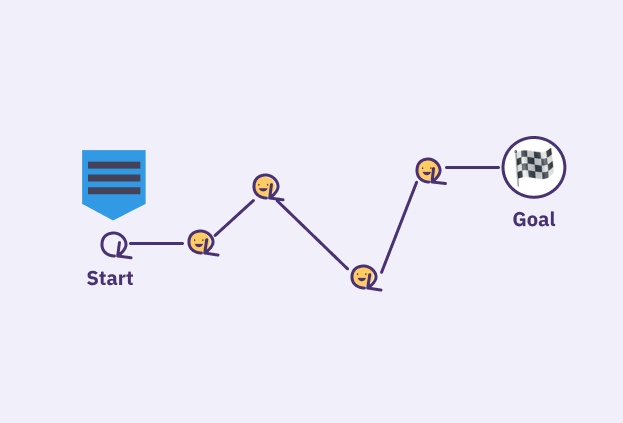

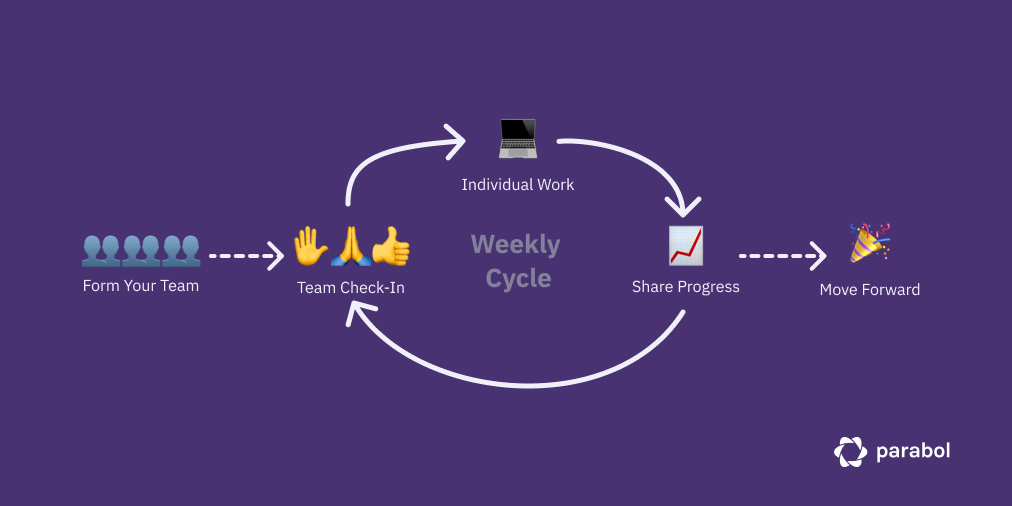

The five simple steps to agile management:

- Assemble your team and set the team’s purpose

- At the head of the week, conduct a Check-In Meeting to make a plan

- After the Check-In Meeting, do work — any way that suites you

- At the end of the week, share an update of your team’s progress with other teams

- Repeat from step 2 until the team’s work is finished

Step 1: Assemble Your Agile Team and Set its Purpose

Teams come together to work on a common cause. However, to successfully navigate uncertainty a team must be open to changing its goals: the focus is not reaching the intended goal, it’s reaching the right goal.

We call the common cause uniting a team the team purpose. A good team purpose statement often answers the question, “why has this team come together?” rather than, “how will this team reach its goal?” We do this to allow the team to change its plans, or even the goal, as it encounters new information.

Examples of a team purpose:

- Good: moving people from point A to point B

- Bad: furnishing faster horse rides

Take care to keep the team size small — to maximize the nimbleness of your try to have no more than 7–10 members. Remember, you can always divide teams into sub-teams, which each share a piece of the common cause.

Step 2: Hold a Check-In Meeting Each Week

A Check-In Meeting is a quick, facilitated meeting to share information, unstick stuck team members, and make a plan for the week.

For many, the notion of having a Facilitator — someone appointed to guide the flow of the meeting — is new. So, why a Facilitator?

We’ve all experienced certain meetings that tend to run astray or run over. Sometimes, a particularly frustrated attendee will “self-appoint” themselves to try to move the meeting along, “come on, we’re over time, let’s wrap this up people…” Having a Facilitator makes it explicit that our time is valuable and staying on track is important.

So who’s the Facilitator? If you’ve read this article and you’re intrigued to try this way of working: congratulations, you’re the first Facilitator. You can always switch to somebody else later — it’s a great way to give other team members opportunities for leadership.

To get started, schedule a 30 minute meeting at the head of the week — either Monday or Tuesday. (Our team favors Tuesdays because there are so many holidays that fall on Mondays, and we favor regularity).

Follow Simple Rules for Agile Meetings

During your first few meetings as the Facilitator, cover all the rules with your team:

- Mind the Facilitator — their job is to move the meeting forward

- Avoid interruptions — only one voice at a time

- Minimize debate — if we discover we need to make a decision, we’ll create an action to make that decision following the Check-In meeting

This last rule, minimizing debate, is important. It reaffirms that the meeting is about making a plan for the week and not making decisions. In a Check-In Meeting, decisions are captured as work so they can be handled after the meeting. (You’ll soon see how…)

Once the rules have been covered, the team can then conduct the meeting in the following way:

Conduct an Icebreaker Round to Start Your Meeting

The Facilitator provides each participant with a moment to answer an icebreaker question, such as “What’s on your mind? What has your attention?”

Their answers might sound like, “nothing, I’m fully present.”, or “I’m stuck against a deadline, I’m really frazzled today” or, “I’ve got a sick kid at home, I’m not completely here.”

- Prompt: What’s on your mind? What has your attention?

- Purpose: serves as a roll-call, as priming for participation, a head-clearer, and group empathy builder

- Time: Around 30 seconds per participant

If you haven’t run an icebreaker round before, or you’re skeptical about them, read up on how icebreakers can help your team.

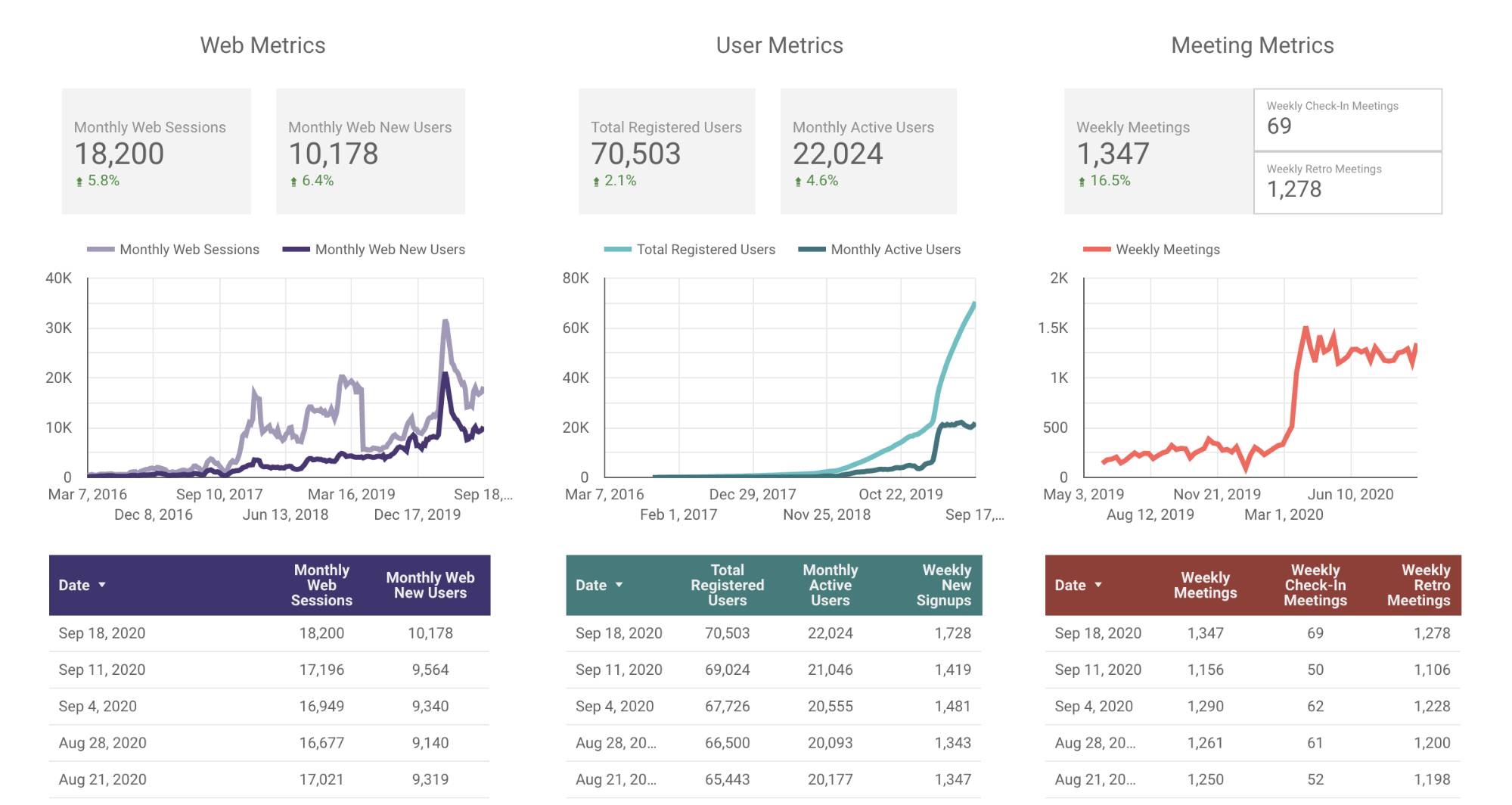

(Optional) Take Time to Review Metrics

If your team is data-driven, a Check-In Meeting is a great forum to review changes in important metrics and surface trends. Examples could include customer satisfaction, engagement, conversions, response times, or anything to keep an eye on that would inform the team’s plan.

Each metric should have a clear owner who is responsible for gathering and reporting the data. When reporting information, try to surface important trends that the team can take action on (such as, “views of our content were up for the third consecutive week”) rather than as numbers without context. Give the team something it can react to.

As the data are presented, the team may ask clarifying questions. If a discussion should arise, the Facilitator should steer it into the creation of an agenda item, perhaps by saying, “that sounds like an agenda item…” (see below: Call for Agenda Items).

As an example, our metrics board looks like this:

- Prompt: What’s changed in our metrics since last week?

- Purpose: surfacing important data to drive new team priorities

- Time: around 5 minutes to report key metrics and answer clarifying questions

Update Team Mates on the Status of Your Tasks

Essential to an agile management practice is to keep a list of tasks. That task board should be open to the entire team, and each project should have a single owner and a status.

Single ownership makes it clear who’s ultimately responsible for delivering a project —eliminating the “I thought you had it!” problem — but doesn’t prevent the owner from working on the project with others. A task’s status keeps it clear to a team how the team’s work is proceeding.

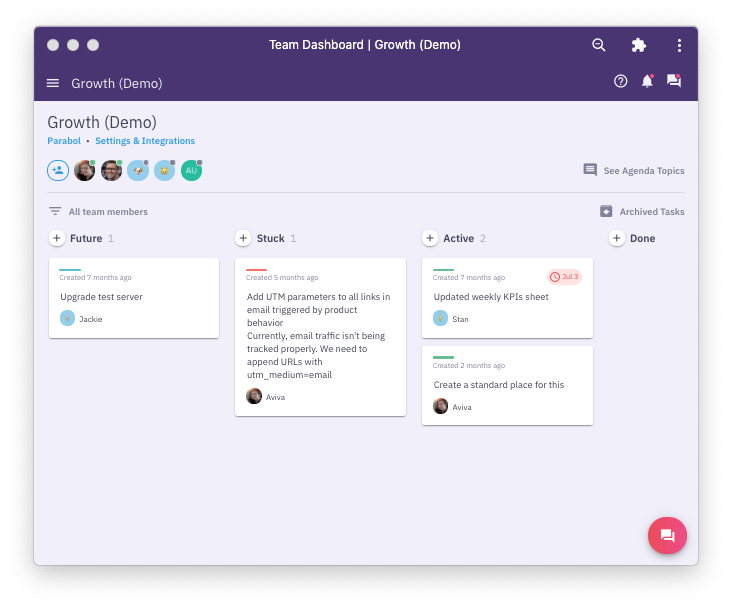

There are four states a project can be in: Active (the owner is presently working on it), Stuck (progress on the project is blocked by someone/something), Done (it’s finished), and Future (de-prioritized until it’s necessary).

During the Updates phase, have each meeting participant briefly spends 1–2 minutes sharing only what’s changed for their projects since the previous week. It should go quickly. If there have been no changes on a project, the team member should say, “no change.”

Here’s what a team’s Project Board looks like using our software:

Other teams also use tools like Trello, MS Planner, or even Google Sheets.

- Purpose: surface data on team progress, especially stuck projects

- Prompt: What’s changed since last week?

- Time: around 1 minute per participant — it should go fast.

Pro-tip: when describing a project, write it in the past-tense so it is clear when it is complete. For example, “video made” vs. “make a video”, see which one is more difficult to argue with when the project is incomplete?

Pro-tip: clear your Done projects at the end of each week to reduce clutter from building up over time

Call For Agenda Items

For the first 15 minutes or so, the meeting has focused on building shared understanding (what the U.S. Marines call “situational awareness”). Now the team will use this understanding to generate a list of agenda items, which will be unpacked into an action plan for the week.

Agenda items are called out by team members popcorn style and recorded by the Facilitator: one or two words are given to describe the item, and when there is silence, the “popcorn” is done popping and the meeting proceeds to the next phase. When an agenda item is given, it’s perfectly fine if it is only understandable by the person saying it. It’ll just be used to jog that persons memory.

The dialog might sound like, “new feature,” “client lunch,” “animated gif”, “documentation,” and so on. A list is then made like this and kept by the meeting Facilitator.

- Purpose: building a list of topics to next be unpacked into a plan for the week

- Prompt: Who has an agenda item? Anything else?

- Time: up to 2 minutes

Process the Agenda as a Team

Once the agenda has been built, the Facilitator leads the team through the agenda one item at a time to build the new weekly plan. The Facilitator always begins by asking the agenda item’s owner, “what do you need?” The team member responds by adding tasks to the team board, when appropriate.

If the team member is making a request of another team member (“I’d like you to take a project called ‘training video made’), the person receiving it is not obliged to accept it—ideally even if the person making a request is a superior. That way, if the receiver is too busy, the work can find an owner who is able to prioritize it. A team member may always make a request of themselves (“I’ll take a project to…”).

If a debate begins over an agenda item, the Facilitator should remind the team of the Minimize Debate rule and instead coach the creation of a simpler next step, rather than try and lead the group to make a decision. Often this is “schedule a meeting to decide X”. Some teams practicing the Parabol Rhythm schedule time following the Check-In Meeting to make decisions while everybody is together.

Often creating new projects and actions will trigger others to contribute new agenda items. This is great! The Facilitator just tacks them onto the end of the agenda list and continues processing the agenda items until the meeting is over. If it’s clear that a team won’t make it through the full agenda before the meeting ends, the Facilitator can always reprioritize the list to their liking.

It’s recommended not to save the agenda for the next meeting so the team can always focus on the most important work in front of it. The adage is, “if it’s important, it’ll surface again.”

- Purpose: unpacking agenda items into requests for teammates, a.k.a. the plan for the week

- Prompt: What do you need?

- Time: up to 1–2 minutes per agenda item, until all agenda items are processed or there is 1 minute left in the meeting

Close the Meeting

To end the meeting, develop your own closing ritual. It can be as simple as the Facilitator saying “thank you everybody, have a great week” or giving everybody a chance to sign-off. We’ve even seen teams close out like a sports team with a single clap.

- Purpose: mark the end of the meeting

- Prompt: (your own sign-off ritual, such as “thank you everybody, have a great week”)

- Time: less than a minute

Step 3: Work Individually

Now that your team’s work is structured for the week, it’s the job of each task owner to make some progress. Following a Check-In Meeting, each team member should review what they need to get done and arrange the rest of their week to make sure they can get what they need to make headway.

Often this takes the form of scheduling working sessions with colleagues or marking off a portion of one’s own calendar as working time. Tailoring your weekly calendar to suit what you need to get done, rather than being subject to an assortment of meetings, will feel revolutionary!

Step 4: Share Progress

Every team has a customer to please, whether external clients, management, or other teams. Creating collective action — punching above the weight of a single team — depends on how well information is shared between teams. The final leg of an agile management process is creating a moment to share a team’s progress.

Effective information sharing doesn’t have to take the form of a slick PowerPoint deck or meticulously formatted document. Something, anything is better than crickets. We recommend a simple note assigned each week to a different team member as a project, called a “Friday Ship.”

The Friday Ship is an email or post on Slack (in a channel called #fridayship) that has two sections:

- This week we… — a list of changes to projects

- Next week we’ll… — a list of requests of what’s coming next

The only thing that matters is that a team’s stakeholders have an opportunity to give informed feedback. For an example of our organization’s Friday Ships, have a look at what we write to our company’s stakeholder each week.

Not a panacea, but a foundation

While team members perform work, frictions will arise. An agile management practice doesn’t solve for every aspect of work. For example, it doesn’t clarify who has permission to do what, or what process to follow for certain kinds of work. For these sorts of challenges, we recommend conducting Team Retrospectives.