Meetings are great

the benefits of intentional synchronous time

It was a crisp fall morning, and I was filled with nerves and enthusiasm about the impending challenge: my first day at a new company.

Unfortunately, within the first month, my initial enthusiasm faded, and I felt increasingly pessimistic about my future there.

The company was a progressive tech company, and followed some hot trends in management:

- The structure was flat – Everyone reported to a duo of leaders, with no additional hierarchy.

- Roles were fluid – While there were different functions, people’s roles on projects were fluid and changed almost daily. People would move to different projects or shift focus constantly.

- There were no standing meetings – No project or function held a regular status or check-in meeting. Changes in roles, scope updates, discussions with leaders – all of these happened in ad hoc hallway or desk-side conversations.

This culture is not unique. In the Future of Work space and among trendy tech companies, many shun meetings and pride themselves on a ‘no-meeting’ culture.

But without meetings, we lose out on something precious: the opportunity for a group working together to share dedicated time and (physical or virtual) space. When you make that investment of time and space wisely, you enjoy outsized gains in a shared context, richer connections, and more effective collaboration.

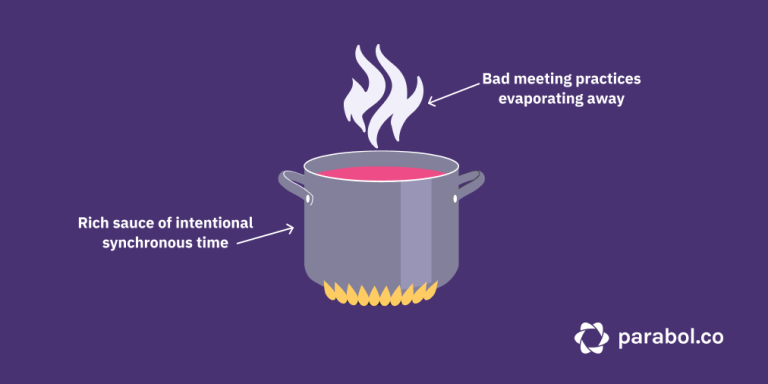

We shouldn’t be optimizing for fewer meetings – we should be optimizing for richer synchronous group time. Like reducing a weak broth into delicious demi-glace, we can let bad meeting practices evaporate away and leave behind something rich and packed full of goodness.

Let’s break down how meetings got a bad reputation and how to avoid those pitfalls, then discuss how meetings can be a force-multiplier (context, connection, and collaboration), and how to structure meetings so you can reap their rewards.

How meetings got a bad reputation: Bad meetings

It’s no wonder people hate meetings – there are a lot of bad meetings out there! In 2019, Doodle (a tool for finding the best time to meet) found that US companies wasted $399 Billion with unproductive meetings with 89% of people saying poorly organized meetings irritated them.

Teams reject meetings when the time spent doesn’t feel worth it (which is what we’re on a mission to stop). Meetings don’t feel ‘worth it’ when teams don’t make good use of the rich bandwidth in synchronous time, include random people, lack structure or don’t serve your ‘real work.’

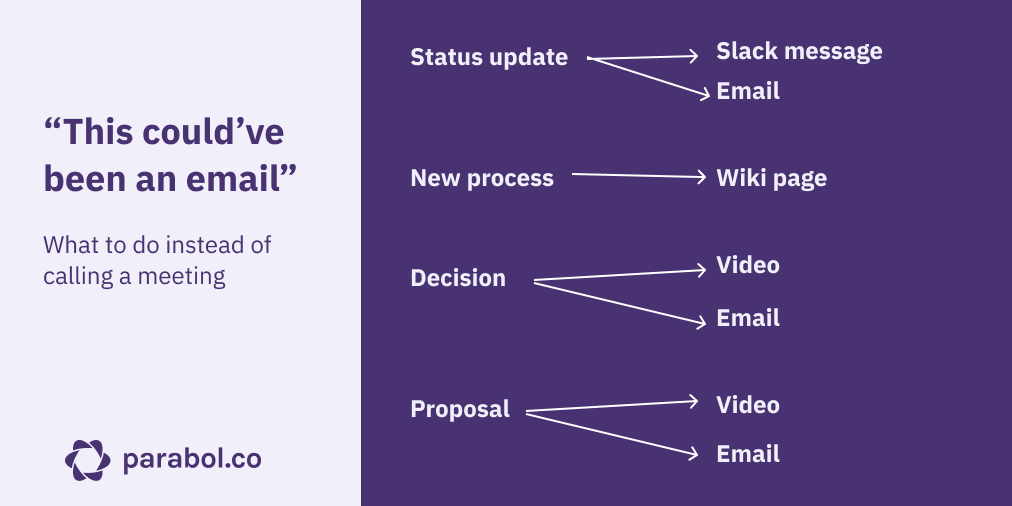

Problem #1: “This could’ve been an email.”

Not going to happen today! No, no, no! #meeting #culture #efficiency pic.twitter.com/g9j03Gl65q

— Elke Guhl (@ElkeGuhl) October 3, 2019

Perhaps the most common anti-meeting refrain is ‘This could’ve been an email.’ When meetings are used to share basic information without interaction from or among attendees, people feel like their time was wasted.

At Parabol, we avoid using meetings to just share status updates, because there are so many non-synchronous ways to share information. When you share information via Slack, an email, or a company wiki, you’re giving the team the autonomy to digest it in their own time, rather than demanding they do it on your schedule. That means they can choose how much time to invest, and are less likely to be resentful.

Many things could, indeed, just be an email.

Problem #2: “Who are all these people?”

Assuming attendees do need to engage with one another, another common pitfall is inviting too many people to the proverbial (and sometimes literal) table.

In a bid for inclusion, everyone possibly impacted by a decision is invited to the meeting. They stand around thinking, “who are all these people?” The meeting results in too many voices, many quiet people, and an ultimately unsatisfying decision. Again, the time invested doesn’t seem worth it.

Synchronous time is a precious investment from all attendees – it’s a truly limited resource. A few powerful ways to be both inclusive and have a productive meeting are:

- Provide opportunities for feedback before or outside of the meeting: While input from many voices is valuable, chances are there’s a small group making the decision. Use asynchronous tools to gather feedback, take time to process it, and then spend your synchronous time on the difficult task of making a decision. Our team gathers feedback from a large group by running an async retrospective with Parabol and then later processing that feedback as a small team to decide how to move forward.

- Clarify the roles of attendees: You may have some folks in the room because they need to understand and communicate a decision to others. You may have others in the room who you are helping level up – they will need to guide similar decisions later, so you want them to see how it goes. At the start of your time together, define everyone’s roles – who is providing input? How is observing? Where does the decision-making authority lie? That’ll help everyone understand who is in the room and why, and value one another’s input.

- Assign a facilitator: Even the most crowded rooms can be productive if the right person is at the helm of the discussion. A neutral facilitator can steer the discussion by supporting folks as they navigate the difficult task of deciding something when they don’t know each other very well.

Problem #3: “What are we doing here?”

When you don’t know what you’re trying to do, it’s hard to do anything well, or feel the time you’ve put into trying was worth it. The easiest way to instill purpose in a meeting is to open it by sharing why it’s being held.

Who participates, how they participate, and what meeting output is gathered should derive directly from the meeting’s purpose. Without these elements, participants can lose sight of the purpose and feel their time was wasted.

The solution here is to provide structure to the meeting:

- For a retrospective meeting, try a tool like Parabol to guide you through an emergent discussion

- For a regular team meeting, try our Check-In format to collaboratively create an agenda and be guided through the process as though you have a digital facilitator

- For other types of physical and online meetings, a variety of tools from Google Docs to virtual whiteboards to Kanban boards can help anchor your discussion

Problem #4: “When do I do ‘real’ work?”

Especially for folks tasked with delivering designs, writing code, crafting copy or creating other hard deliverables, the outcomes of a meeting feel rather abstract in contrast to their defined duties. Participants see their ‘real work’ as designing, coding, writing, etc., and thus meetings are distractions from ‘real work’.

But we can’t do truly great work without truly deep collaboration with one another. That’s why we form teams and companies – to take on projects bigger than ourselves, sail stormier waters, and scale taller mountains.

Participants may complain about not having time for real work when it’s unclear how the meeting serves them. Perhaps the meeting supports a leader’s need for gathering information, but not not the individual’s need for feedback on the information they’re sharing. Alternatively, perhaps their schedule is so packed with meetings that they are having a hard time finding the long stretches of time they need for deep work.

To solve this problem:

- Define the purpose of each meeting: For a meeting to exist, someone had to call it, which means they had an intention about how that time would be spent. That person can share their intention, and the team can discuss whether that’s truly happening and, if not, brainstorm alternatives. It’s also an opportunity for the team to agree to spend time on that purpose – a meeting for a leader’s benefit isn’t a problem if the team also values that leader having the information they’re sharing.

- Run a retrospective on your meetings and schedule: I realize that recommending retrospectives so much starts to feel like a broken record, but they are the best format I’ve found for processing feedback from many participants and getting to action quickly. In a retro, participants can share what their true tension around meetings is – are they missing time for deep work? Are they not getting what they need from the meeting? This feedback allows you to address the true concerns of your team, rather than guessing at what’s not working for them.

Even though we make a meeting tool, at Parabol, we only spend about 7% of our time in internal meetings. We can do that because we’ve created a meeting rhythm that truly serves our work – our synchronous group time is a rich mineral we’re mining for all we can.

Intentional, synchronous time creates shared context

With an understanding of how meetings got a bad reputation, we can now talk about what you’re missing out on when you have bad meetings, and how to take advantage of your shared sync time.

Meetings mean a group of people is sharing time and (physical or virtual!) space. That’s a rare opportunity to deeply understand what one another is doing, ask questions and get rich answers, and generally develop a shared reality.

That shared reality is critical to the teams’ success.

In a crisis, getting on the same page is vital to acting wisely and swiftly

I was leading a division and tasked with making some big changes to drive big results. As was typical of our company, we’d pushed forward quickly to ship something – erring towards action rather than caution.

Unfortunately, the bet wasn’t an obvious win. I hadn’t considered how one of our user segments would respond to the change, and we were surprised by a ton of feedback during the public beta phase. Because it impacted my division, other products, and our reputation, as the leadership team, we knew we had to act fast.

Fortunately, the response coincided with an in-person retreat for our team. Each morning, we gathered around the conference room, spoke about the latest replies, asked one another questions, and determined our next steps. The folks in the room were a diverse group, including some that had been in that market for a decade and some that were fairly new. As more experienced folks shared some context about the implications of our decisions in the market in general, we were able to craft smarter, faster plans of what to do next.

Ultimately, we were able to respond to the feedback, reassure our teams, and make changes to the feature to satisfy our users’ concerns and also move the product in the direction we wanted. I couldn’t have done that without real-time feedback from the rest of the team. By getting together in real-time, teams navigating urgent decisions can get up to speed quickly and respond swiftly.

If you’re running into an urgent issue, get on a call together right away. Chances are, if the issue is big enough, no one’s thinking about anything else, and being in one space together will let you understand what’s going on with each person much more quickly.

To pass off work, teams need a shared understanding of what they’re doing

I was working with an engineering manager who wanted to get the developers working more closely on architecture and technical issues. The team had been together for a while but were each doing largely individual work. This new manager wanted his team to learn from one another and be greater than the sum of their parts.

To start, he implemented a ‘bug triage’ meeting – the developers would go through tricky bugs he’d picked and try to solve them together or at least understand them. The team was stretched from Poland to the Pacific, so this synchronous call was one of only two hours they spent all together in a given week.

Over time, the meeting morphed into a ‘developer roundtable’ as developers started appreciating the group input and brought their own questions to the meeting. They enjoyed getting deep feedback, peer working proposals, and sharing their work with a team that truly understood what they were wrestling with. As a result, every member had a richer understanding of what was going on across the code base and each could contribute to any issue or review any PR on the team.

For a team to work as a unit, they need a shared understanding of their work. Working together in real-time provides a richer understanding of shared work than any other format.

Intentional, synchronous time builds connection

Another critical benefit to intentional, synchronous time is the connection between team members. When everyone is gathered in one place (including virtual spaces!), team members can start to build connection as they interact with one another.

You can structure meetings to deliberately foster more connection.

Icebreakers allow for a bit of humanity that builds rapport & trust

In a remote setting, there’s no chance encounters at the coffee cart or drinks after work. If you want to connect, you need to find time for it. But even with co-located teams, people can often work together for years and still miss out on those chance encounters because, even though you’re on the same team, your desks are far away, or even in another building.

Meetings are already a time you spend together, so they’re an obvious place to inject some bonding opportunity, and one way to do that is with an icebreaker question.

That’s one of the ways we became closer on the previously-mentioned leadership team. The team had been working together for 6+ months, yet everyone seemed somewhat stressed and we weren’t talking to each other much about what was stressing us out. In each of our twice-weekly calls, multiple people would drop hints about feeling overwhelmed, but those mentions metaphorically fell flat on the floor as we moved on to the next Important Topic.

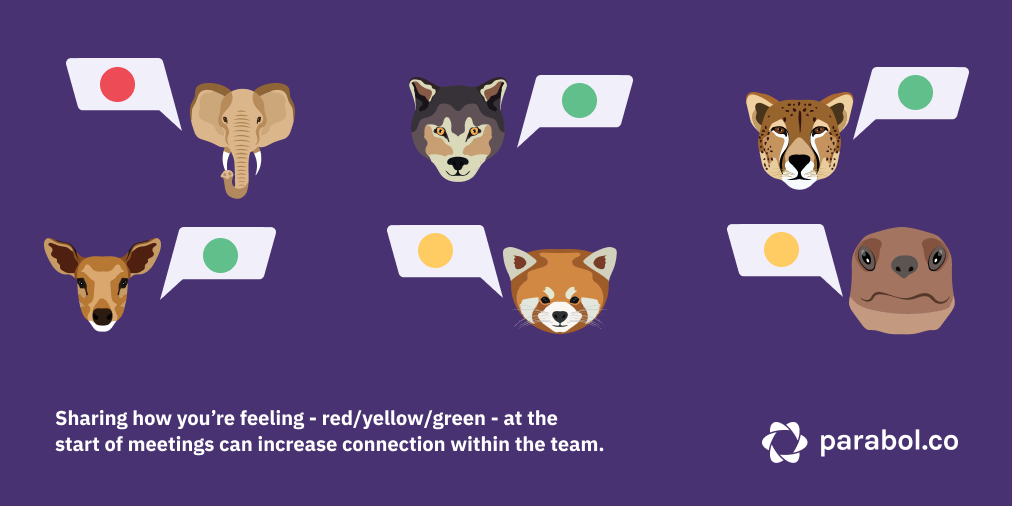

To start having more human conversations, we implemented a red/yellow/green check-in at the start of meetings, just to create space to acknowledge the stress. We’d go around the Zoom screen and everyone would say how they were:

- Green – I’m present and ready for this meeting

- Yellow – I’m here, but aware of some things to address

- Red – There’s something drawing my attention away from this discussion

Each participant was free to just say their color, or share some explanation if they felt compelled. Over time, we started to notice and ask about the underlying reasons, and build empathy and care for one another.

We shared difficult dynamics in our teams that were weighing on us, explained stressors in our personal lives that distracted us, and were able to help each other navigate those challenges.

By adding a lightweight question to our real-time interactions, we had the opportunity to share a bit about ourselves, and get closer.

If you’re stumped by how to do this yourself, we have 300+ questions you could try out.

Sharing activities allows you to build relationships

While working previously at another fully-distributed organization, our remote team got together 2 times per year for in-person retreats. These were meant to help troubleshoot issues and build a sense of community. Think of these as team retreats or multi-day meetings.

During these, our team got a taste for escape room games. In one week, we’d played more than 5 of these Exit Games, and also did escape rooms. This was an opportunity for everyone to work together on something outside of our normal roles. That meant we got to know each other, how we work, what our strengths are, in a different context.

In a truly ironic twist, one of the games had us split into teams and compete against each other. The final puzzle required us to work together to actually get out of the room. All of the developers refused to collaborate, and one of my team members instead used his electrical engineering knowledge to figure out how to open the door without solving the puzzle. That told me a lot about how much we all valued winning!

The experience was so bonding that I brought Exit Games to the Parabol team at our last S.P.A.

Outside of a retreat like S.P.A., teams can set aside time to play games together during the week or incorporate quick games into some team meetings. This intentional time spent together will reap rewards in team cohesion, and pay off in ways unimagined.

Intentional, synchronous time fosters collaboration

Along with context and connection, intentional time together allows teams to start truly working together. While defaulting to async will empower remote or dispersed teams to get more done quickly, to put together the truly complex puzzles, you’ll need some real time together.

Good planning depends on bringing together divergent perspectives

At the start of an agile sprint, it’s common for engineers, designers and product managers to meet and move issues from their backlog into their sprint. It’s so common, we likely don’t think much about why we do it this way.

I, however, was new to agile. I was working closely with an engineering lead who wanted to move to an agile process. I wasn’t sure why we should all meet together to plan. Wouldn’t it be easier for one person to do it? And, being a bit of a controller, wouldn’t it be best if that person was me?

But I trusted the process and agreed to yet another weekly meeting.

I met with engineering and design leads to plan the work we’d do in the next sprint. We collectively decided which items were high priority and what we needed to get done. Each member held a different perspective – I considered business goals and customer research, designers focused on improving the overall experience, and engineering leads focused on making sure developers had what they need to complete the given work well. By each holding a piece of the puzzle and working through it in synchronous time, we could get to better-planned sprints.

Without collaborating in real-time, our planning would’ve taken much longer, as we tried to remember and negotiate each decision over the course of days. Similarly, if one person had done it, whichever perspectives weren’t included would’ve felt shortchanged.

Meetings are a time to bring together different perspectives. Since each participant holds a different set of puzzle pieces, the act of putting them together in real-time results in a more interesting puzzle.

To make and follow through on tough decisions, stakeholders need to buy-in to the plan

I logged on one day to find a shocking decision waiting in my inbox: a popular product was no longer a priority for the company, and the product team wanted to sunset it.

The problem was that it still had a meaningful user base.

Quickly, representatives from support and marketing started expressing worries. What would customers who depend on this product do? Why couldn’t we serve them?

Without immediate access to the product team, we brainstormed solutions on our own. Could we open source it? Could we find a contractor to do the work? What if we built something new that would serve the same customers?

The frenzy built and we couldn’t get to a resolution until we all sat down to talk in person, in real-time.

Around a conference room, each group could voice their concerns. The product team was able to explain the intricacies of their choice, and we collaboratively developed a plan of action that would suit everyone’s concerns.

Without the shared time to dive deeply into each aspect, we were going around in circles. We needed the real-time experience to get to a solution.

Meetings are an opportunity to hear and be heard and then get immediate feedback on what’s been said. Intentional, synchronous time allows teams to process different perspectives more quickly and find innovative solutions.

Meetings can be a first step towards something smarter

For all the benefits of intentional time together, meetings are still not always the best tool for solving a certain problem. Because they’re familiar to all of us, like a person with a hammer, every problem looks like a nail, and so we use meetings to solve all manner of problems they’re not needed for.

However, because they allow for rich interactions, meetings can be a good first step towards building a smarter process. As a bonus, in just doing the meeting, you gain context, build connection and start to collaborate – all of which makes future efforts much easier.

I ran into this idea when I was invited to a 2-hour weekly meeting with 20+ attendees. Nothing sparks less joy than being invited to a long, large meeting on an ongoing basis.

The reason behind the meeting was fuzzy too. The design division recently hired a new leader, and he spotted a problem we were all familiar with – designers weren’t working together very well across different products. This weekly meeting was his tool for creating connections among designers and product leads across the organization.

It was cumbersome and complicated, and it worked as a first step.

As a product lead, I personally gained context on what was going on in parts of the business I didn’t work with, and also an understanding of the priorities for design as a discipline at the organization. I could also share the perspectives and concerns unique to my part of the business. Over time, we all spoke more intelligently about our work in the broader organizational context, and we started connecting and talking outside the meeting.

We could’ve tried communicating async, but I imagine things would’ve been slower:

- Designers presenting work would need to imagine potential questions or take days to respond to feedback, rather than getting them in one bite. Folks responding earlier would’ve missed the context of later questions.

- Product Leads likely would’ve responded to discussion directly relevant to them and their part of the organization, as they weren’t forced to sit through other conversations. We would’ve missed creating connections or collaborating with new folks.

Because we are all busy, the blunt-force tool of bringing people together into one virtual space in real-time made us pause and notice one another, lifting our head out of the fog to see what else was going on.

If you’re struggling with a complex problem, especially something in the culture of your organization, there’s rarely a better first step than finding a way for relevant parties to talk about it together. By setting up an ad-hoc meeting or a time-bound commitment to experimenting with a meeting for a certain period, you can kickstart your path to a solution, and save finding the “right” process for afterward.

Don’t avoid meetings – start spending intentional time together that feels worth it

Meetings can, indeed, be a waste of time. Whether they could’ve been an email, included too many people, had no set structure, or overwhelmed your schedule, bad meetings can suck the spark out of a team.

But if we can reframe a ‘meeting’ and instead think about the unique power of getting a group of people to interact synchronously with the intention of doing something, we can unlock the power of something pretty profound.